Ian coulson - curator

All the artwork shown here by artists of the Creative Network has been produced in response to the ideas and the feelings that are excited by thoughts of HOME.

Islanders have a firm and fixed idea of what and where home is because we grow up with an implicit awareness of where the physical edges of it are. Which ever way you are facing on the Isle of Man, you know which bit of coast is behind you or to your right or left. In my previous life as an art lecturer as part of my farewell talk to students leaving to study at degree level in the UK, I would warn them of the probability of the appearance of homesickness within their first term away. Some found this startling because their unquestioned access to ‘home’ and ‘family’ and all of the emotional support and reassurance that these entailed, had never been challenged. Whilst in the security of your native environment the old one liner, ‘I’m homesick……….. I’m home - and I’m sick of it’, can raise a laugh - but not so readily when feeling alone and away in a strange city trying to make your way amongst new acquaintances, when the yearning for your native sod can be sometimes overwhelming. As a young art student, newly arrived in the English Midlands, I couldn’t account for my own persistent unease and it was only some weeks later that, having hitch-hiked to Brighton, I saw the English Channel in all its snot green coldness, heard the familiar white noise as waves sucked out through the shingle and I simultaneously tasted the reassuringly rotten smell of seaweed and salt in the back of my throat, I had a monumental epiphany… I had missed the thing that had been there all of my life and in Loughborough I was further from it than anywhere else in Britain…. THE SEA! Every weekend from then on found me at the coast topping up on enough ozone to do me for the next five days.

I have a friend who, during her itinerant childhood, had made the perspicacious statement that has passed into her family lore that, “Home is where the suitcases are…”. This represents the polar opposite to my own experience. Growing up is sometimes something of a brutally competitive experience within the juvenile cohort. You have to carve out, and continuously defend, a space for the idea of ‘yourself’ as you daily develop and try to understand it. Growing up ‘arty’ in a fishing village in the 1950s, if you were to remain true to yourself, meant that your perceived unconventionality was always received as wacky eccentricity and all difference was suspicious. Consequently, as a young person I often felt an outsider in my own town. Then as now, other children sense difference or weakness in their peers as readily as though it were carried on the wind. Almost invariably, a ‘ganging-up’ results in which the

conformity of the group is expressed; blunt conformity triumphs over complexity and the group feels strengthened. Who knew then that this is a tempering process that most creative individuals undergo during their childhoods? From it they gain the strength to overcome societal pressures towards the safe, the average and the predictable. So, although Peel and by extension the Island, has always been my home, it has not been invariably nourishing and we forget the trials of our own upbringing at the possible costs to our own children’s experiences. Parents in Peel were mostly absent during the day - mine both out at work for long hours in the fish, so although ‘The Lord of the Flies’ tendencies could flourish unhindered amongst the free range young in the town. It also meant that all kids and dogs would wander far and wide, unhindered across the whole landscape and say at eleven years old, and with the arrival of one’s first bicycle, true geographical freedom was achieved. This was heady stuff and I embarked upon what has turned out to be a life long fascination and heart-felt attachment to the Island’s topography and landscape, its life and culture and its history and place-names.

I sat the other day looking down into the street from the first floor dentist’s waiting room and watched as, at intervals, perhaps ten kids of early teenage crossed the road at the lights, hand in hand with their mothers. Life is perhaps more cosseted now for our children, and inevitably their concepts of ‘HOME’ will develop differently. I was warmed by the parental hand holding but I feel for our young people with their exposure to the anonymity and viciousness of cyberbullying. I at least knew the faces of my few intermittent tormentors; but how will the young develop their intimate relationship with the ground beneath their feet without the freedom to wander about ‘untracked’?

I was gobsmacked as a young art student, by the realisation that it was up to me entirely what I made work about, that it was the artist who chose the ideas and initiated the means that brought work into existence and consequently determined what ART was. So given complete freedom to do or make anything at all - where do you start? Often with what interests us the most…. That is ourselves as a means of self exploration perhaps - and then by extension the things and the places that we love, our home. It is axiomatic to the native Manx, yet still easily understood by people who choose to live on the Isle of Man, that in many ways the place defines us and we define the place. This conceptual ‘unity’ of the human and the geographical is actually ‘as old as the hills’, you need only look at the poetry of Manx place names to feel the historical connection of generations of people who have lived before us in our very houses and shaped this our landscape and who have worn themselves out to feed their families from its agriculture and its fishing. This isn’t romantic tosh, put your hand on a field gate post and you are literally connected to the lives of those who have passed in and out of that field with carted harvest coming out and animal shite or seaweed going in at eight pollags to the cart load. My work of the last few years is rooted in Peel and the fading history of the fishermen whose deeds at sea, either at the nets or in the Navy in times of war, are almost incredibly arduous and extreme to today’s ideas of work in Peel. Such hardship and fortitude to earn a crust and feed a family, such skills in boat handling and navigation that held no social kudos within the town, such simple faith in the face of the most dangerous job in our industrial pantheon, define a way of life just beyond the horizon of our contemporary experience. These were hard hard men whose lives and deeds I wish to memorialise, we can still name them, they lie in Peel cemetery and their descendants live on in the town. My home of Peel is for me an historical continuum generations deep and like the field gate post, I need only shut my eyes down by the harbour to feel this connection back through the human experience of where my home and the sea become one.

Islanders have a firm and fixed idea of what and where home is because we grow up with an implicit awareness of where the physical edges of it are. Which ever way you are facing on the Isle of Man, you know which bit of coast is behind you or to your right or left. In my previous life as an art lecturer as part of my farewell talk to students leaving to study at degree level in the UK, I would warn them of the probability of the appearance of homesickness within their first term away. Some found this startling because their unquestioned access to ‘home’ and ‘family’ and all of the emotional support and reassurance that these entailed, had never been challenged. Whilst in the security of your native environment the old one liner, ‘I’m homesick……….. I’m home - and I’m sick of it’, can raise a laugh - but not so readily when feeling alone and away in a strange city trying to make your way amongst new acquaintances, when the yearning for your native sod can be sometimes overwhelming. As a young art student, newly arrived in the English Midlands, I couldn’t account for my own persistent unease and it was only some weeks later that, having hitch-hiked to Brighton, I saw the English Channel in all its snot green coldness, heard the familiar white noise as waves sucked out through the shingle and I simultaneously tasted the reassuringly rotten smell of seaweed and salt in the back of my throat, I had a monumental epiphany… I had missed the thing that had been there all of my life and in Loughborough I was further from it than anywhere else in Britain…. THE SEA! Every weekend from then on found me at the coast topping up on enough ozone to do me for the next five days.

I have a friend who, during her itinerant childhood, had made the perspicacious statement that has passed into her family lore that, “Home is where the suitcases are…”. This represents the polar opposite to my own experience. Growing up is sometimes something of a brutally competitive experience within the juvenile cohort. You have to carve out, and continuously defend, a space for the idea of ‘yourself’ as you daily develop and try to understand it. Growing up ‘arty’ in a fishing village in the 1950s, if you were to remain true to yourself, meant that your perceived unconventionality was always received as wacky eccentricity and all difference was suspicious. Consequently, as a young person I often felt an outsider in my own town. Then as now, other children sense difference or weakness in their peers as readily as though it were carried on the wind. Almost invariably, a ‘ganging-up’ results in which the

conformity of the group is expressed; blunt conformity triumphs over complexity and the group feels strengthened. Who knew then that this is a tempering process that most creative individuals undergo during their childhoods? From it they gain the strength to overcome societal pressures towards the safe, the average and the predictable. So, although Peel and by extension the Island, has always been my home, it has not been invariably nourishing and we forget the trials of our own upbringing at the possible costs to our own children’s experiences. Parents in Peel were mostly absent during the day - mine both out at work for long hours in the fish, so although ‘The Lord of the Flies’ tendencies could flourish unhindered amongst the free range young in the town. It also meant that all kids and dogs would wander far and wide, unhindered across the whole landscape and say at eleven years old, and with the arrival of one’s first bicycle, true geographical freedom was achieved. This was heady stuff and I embarked upon what has turned out to be a life long fascination and heart-felt attachment to the Island’s topography and landscape, its life and culture and its history and place-names.

I sat the other day looking down into the street from the first floor dentist’s waiting room and watched as, at intervals, perhaps ten kids of early teenage crossed the road at the lights, hand in hand with their mothers. Life is perhaps more cosseted now for our children, and inevitably their concepts of ‘HOME’ will develop differently. I was warmed by the parental hand holding but I feel for our young people with their exposure to the anonymity and viciousness of cyberbullying. I at least knew the faces of my few intermittent tormentors; but how will the young develop their intimate relationship with the ground beneath their feet without the freedom to wander about ‘untracked’?

I was gobsmacked as a young art student, by the realisation that it was up to me entirely what I made work about, that it was the artist who chose the ideas and initiated the means that brought work into existence and consequently determined what ART was. So given complete freedom to do or make anything at all - where do you start? Often with what interests us the most…. That is ourselves as a means of self exploration perhaps - and then by extension the things and the places that we love, our home. It is axiomatic to the native Manx, yet still easily understood by people who choose to live on the Isle of Man, that in many ways the place defines us and we define the place. This conceptual ‘unity’ of the human and the geographical is actually ‘as old as the hills’, you need only look at the poetry of Manx place names to feel the historical connection of generations of people who have lived before us in our very houses and shaped this our landscape and who have worn themselves out to feed their families from its agriculture and its fishing. This isn’t romantic tosh, put your hand on a field gate post and you are literally connected to the lives of those who have passed in and out of that field with carted harvest coming out and animal shite or seaweed going in at eight pollags to the cart load. My work of the last few years is rooted in Peel and the fading history of the fishermen whose deeds at sea, either at the nets or in the Navy in times of war, are almost incredibly arduous and extreme to today’s ideas of work in Peel. Such hardship and fortitude to earn a crust and feed a family, such skills in boat handling and navigation that held no social kudos within the town, such simple faith in the face of the most dangerous job in our industrial pantheon, define a way of life just beyond the horizon of our contemporary experience. These were hard hard men whose lives and deeds I wish to memorialise, we can still name them, they lie in Peel cemetery and their descendants live on in the town. My home of Peel is for me an historical continuum generations deep and like the field gate post, I need only shut my eyes down by the harbour to feel this connection back through the human experience of where my home and the sea become one.

The Peel Nickey ELVIRA according to Mr Radcliffe Quilliam of Peel who was aged 76 in 1945 held the record for the passage home from Lerwick at the end of the Shetland fishing. She made the trip of almost 600 miles in only 57 hours so she must have had a strong Nor’easterly wind all the way down giving her good reaching and flat water off the West coast of Scotland. This trip would usually take a couple of weeks and may even take six weeks with contrary winds. Elvira along with many other fine boats was laid up in Peel harbour during the depression that followed the Great War and Percy Moore and his father Thomas of T. Moore and Sons bought several of them

and cut them up for building timber and firewood. The timbers from ELVIRA were incorporated in the smoke houses that they built in their yard in Factory Lane behind their Michael Street fish shop. I have smoked kippers in those smoke houses before they were demolished so I have a direct connection with the ELVIRA!

and cut them up for building timber and firewood. The timbers from ELVIRA were incorporated in the smoke houses that they built in their yard in Factory Lane behind their Michael Street fish shop. I have smoked kippers in those smoke houses before they were demolished so I have a direct connection with the ELVIRA!

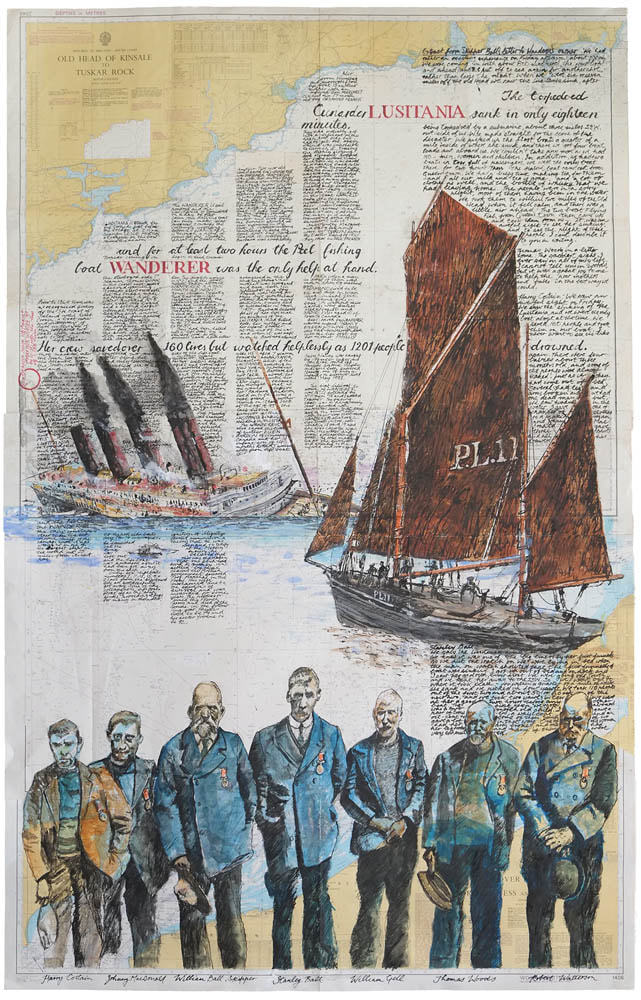

PL11 was the only other vessel present when a German submarine torpedoed the LUSITANIA one of the biggest ships in the world off the Old Head of Kinsale, not 25 miles from her next port. It was a windless day of flat calm and the WANDERER having no engine could only make slow progress towards the calamity unfolding before it. The LUSITANIA kept moving ahead, listing progressively to starboard and in only 18 minutes drove herself beneath the surface. Very few of her lifeboats were successfully launched and for those in them the WANDERER is their point of focus, the first to get to the fishing boat, lifeboat number 21 and the first person handed aboard was a two month old child…. For at least two hours the WANDERER was the only boat on the scene, during this period she took aboard and save 160 lives, in this drawing I have incorporated all the research that I could find about the children that they saved. The named crew take up the lower part of the drawing on the occasion of being presented with medals at Tynwald Day, the newspapers commented upon their pride but look at them, they have watched helplessly as 1201 people drowned, I think that they look haunted.